Way back in the late 1970s when National Geographic came out with the famous hang gliding article that sparked the heyday of that sport, local San Diego pilots were looking for places to launch their gliders. One of the best and most consistent was a little piece of land on a hill, up near the head of Blossom Valley.

Far enough east of the ocean that it doesn’t get shut down by cool ocean air on a daily basis and positioned equally well westward of the local scorching hot desert, Blossom is nestled in a band of air that consistently provides the right conditions for free flight.

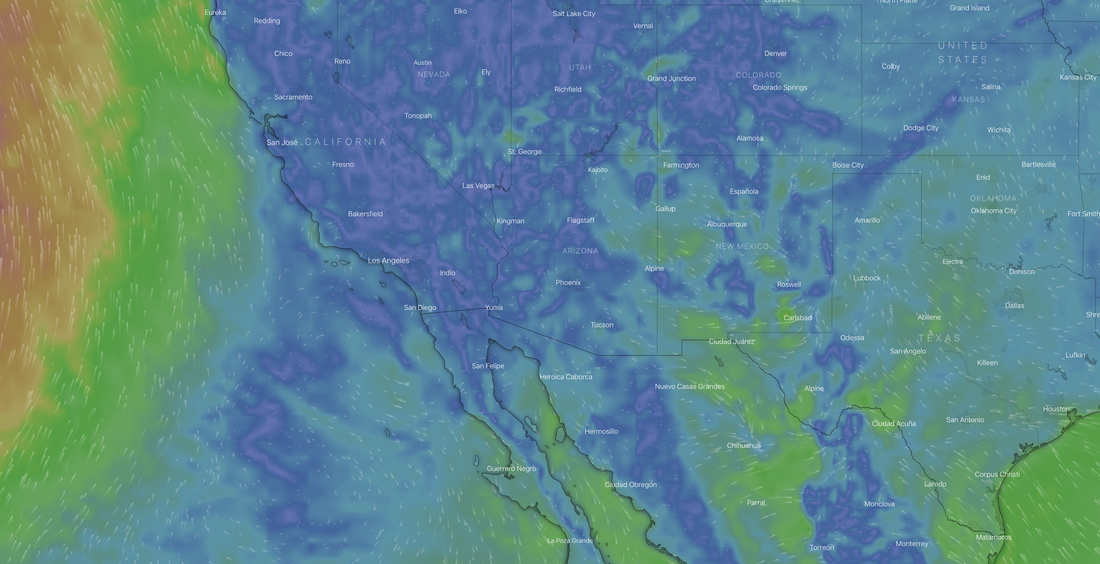

Zooming out even further, Blossom sits in a part of the world generally protected from huge low pressure swirls barreling through. This positioning has made the San Diego area world famous for some of the most perfect weather in the world.

Here's a blustery winter day, with San Diego protected and tempered by ocean and mountains:

Back in those early days of free flight the pilots were, well, a little more radical. They’d launch into conditions knowing far less than we do today about what the day might bring. Some of them got hurt, or scared, or lost interest in flying, but a handful stuck with it, got better, learned to ride the wind and sun with more skill, and kept flying this glorious little site.

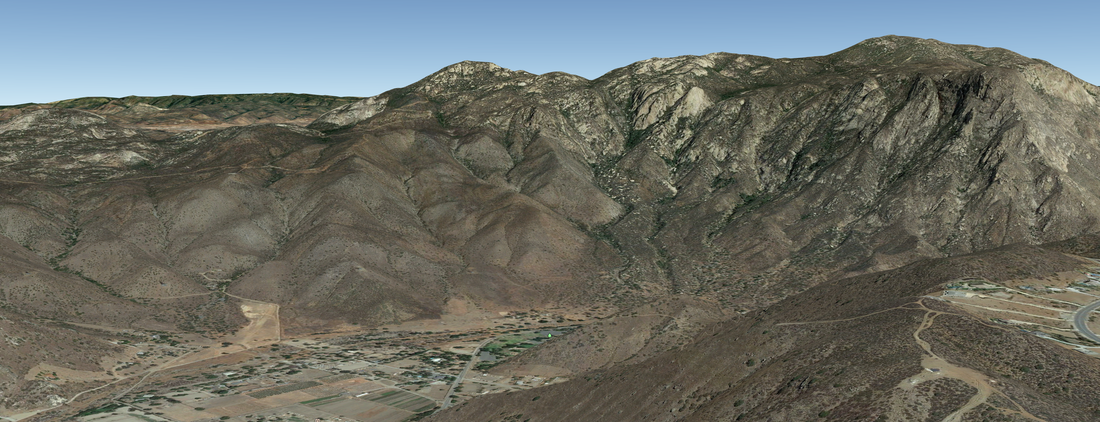

As they launched off Blossom and climbed up in both ridge lift and thermals, they saw the obvious feature across the valley off to the north: El Cajon mountain and the cliffs of El Capitan ("El Cap" or “The Cap”), named after the far more famous rock up in Yosemite.

As the technology progressed, El Cap runs became easier and easier, and the lure of launching off the little hill of Blossom, catching a thermal a few hundred feet up and gliding across a beautiful valley to a stunning mountain on the far side, then flying back, became a magnetic draw for local hang glider pilots.

Local residents started calling the hill they launched from “Hang Glider Hill”, and still do today. Of course, it wasn’t just hang glider pilots that used it. There were off road enthusiasts, people flying remote control (R/C) planes, and eventually, paraglider pilots.

With a wing that could fit in a backpack, paragliders came on the scene and went through the same steady advance in technology until Blossom became known as one of the better places in San Diego to practice the basics of cross country paragliding: Launching, climbing up in a thermal, “going on glide” from the top of the thermal, crossing a valley, then climbing ridge and thermal lift on the far side over at the Cap and finally returning back and landing where you started became a standard "milk run" for progressing pilots.

Most of the time this didn’t happen, but a North wind was a known risk and one that pilots accepted if they decided to make a Cap run.

Of course, part of the lure of free flight is interacting with nature, and pilots would routinely fly with red-tail hawks, turkey vultures, ravens, crows, and golden eagles. One of the most thrilling experiences for any pilot was to catch a thermal and have these magnificent birds fly over to circle around wing-and-wing as you both rode the rising air.

SDG&E and The Sunrise Power Link

As San Diego grew over the years and needed more and more electrical power, city and power planners ignored the obvious but expensive power streaming from the sky (solar) and opted to wire in power from out of the area. This hotly debated but eventually successful push created the Sunrise Power Link, a long swath of gangly aerial power lines that cut across some of the most beautiful and wild land in San Diego.

Fought intensely by environmentalists, SDG&E were forced to make some concessions, one of which was to buy and protect “offset” lands. This meant that in order to balance out the wild and beautiful lands they were running their power lines through, they needed to protect from development other wild and beautiful lands, as well as provide funding to support that protection.

The San Diego River Park Foundation

Started in 2001 in response to the largest sewer spill in California’s history, one that dumped 34 million gallons of untreated sewage into the San Diego River, the SDRPF was created to help change San Diego’s relationship to its namesake waterway.

A scrappy little organization, they steadily built a following of volunteers committed to protecting and improving the river. As they grew, they began to partner with other organizations and work together with non-profits, volunteers, local business, and government entities in order to manage and protect this gorgeous and unique thread of water connecting the mountains to the ocean.

Their mission is to create not just a better understanding, but a better relationship through interaction between humans and the river.

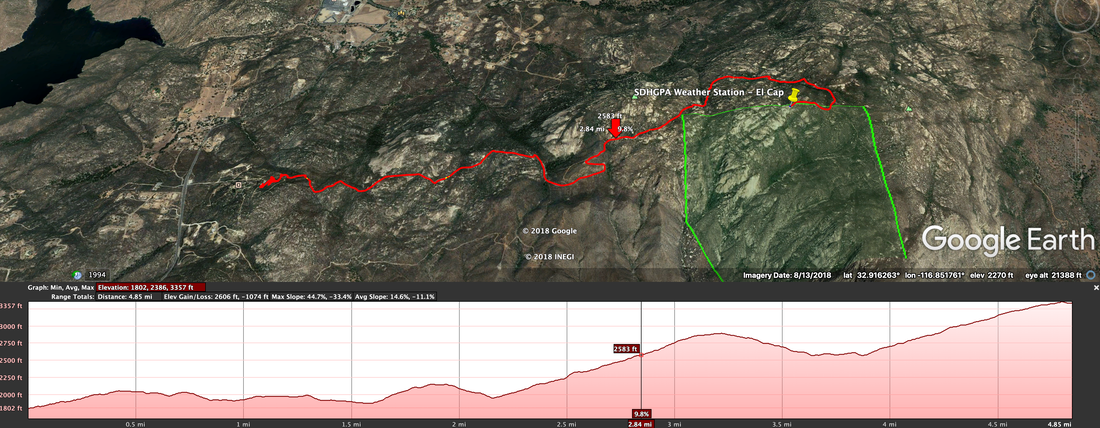

In 2013, the San Diego River Park Foundation was able to begin buying huge chunks of El Cajon mountain (highlighted in green in the picture below) with assistance from the County of San Diego and support from volunteer donations. The area was known to be habitat for an endemic and rare plant species, Lakeside ceanothus (Ceanothus cyaneus), as well as a nesting and foraging area for golden eagles.

Look closely and you'll see the basket dangling at the end of a long line under the helicopter in the picture.

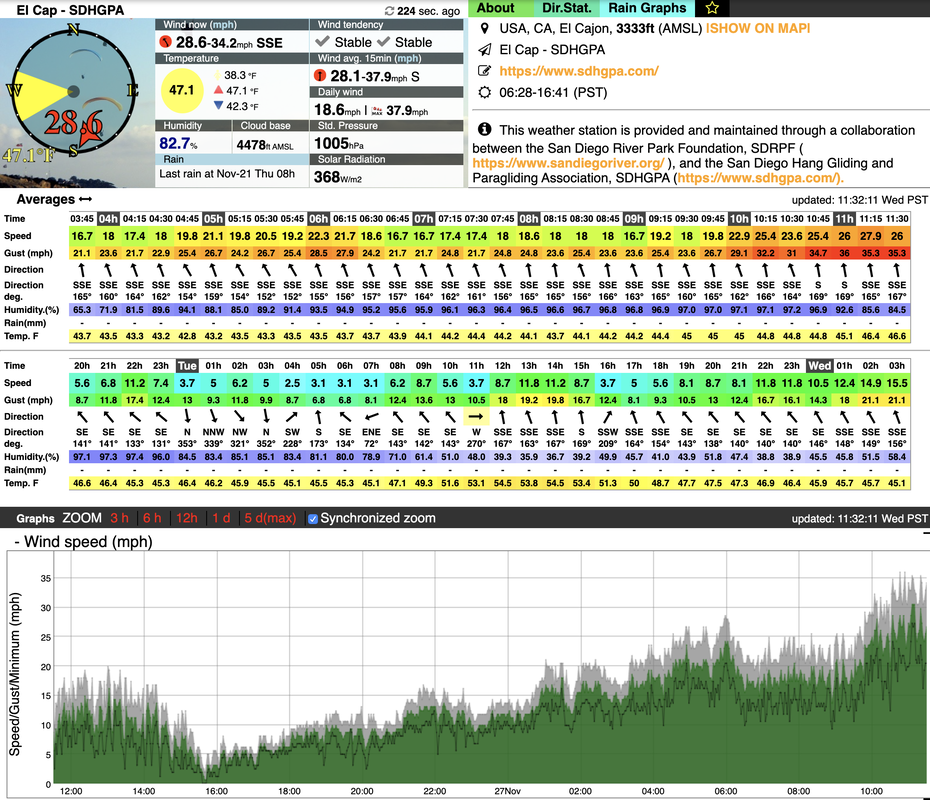

One thing no one had about the mountain was a consistent source of weather data. The amount of rainfall, solar radiation, wind direction and average speeds were all fuzzy numbers, relying on extrapolation from surrounding weather stations, none of which was placed at the same elevation as The Cap.

It was at this point that SDHGPA identified a possible partnership opportunity that would benefit all involved. As free flight pilots, we are totally dependent on weather conditions to allow us to fly. Consequently, we end up being amateur meteorologists and fascinated with weather data.

SDHGPA has been putting up advanced weather stations from Holfuy at our launches around San Diego County. These stations help us predict what conditions will be when we arrive, and can often save us a long drive only to find out that a launch isn’t, well, launchable.

For years, the closest weather station to the Blossom launch was BVYSD, half a mile south of launch and a few hundred feet lower, tucked into a little valley that distorted what the winds were usually doing. We pilots had learned to read the weather station data by adding in an offset for wind direction and speed, but it wasn’t always reliable.

Based on the premise that having a weather station over at The Cap would allow us to make predictions about conditions both over there and back at launch itself, and that those predictions might save us flying into an unknown yet hazardous North wind, we approached SDRPF about placing a weather station on their land.

As it became clear that this weather data would be of equal benefit to more than just us pilots, we decided to add more sensors to this weather station. Typically we get sensors that detect wind direction and speed as well as temperature. This time, in order to maximize the opportunity that this weather data collection point represented, and with additional financial support from SDRPF, we added pressure, humidity, rainfall, and solar radiation sensors.

Having this extra data is also beneficial for pilots, for with pressure and humidity we can predict cloud-base, or the elevation at which clouds begin to form (that marks the top of usable lift for us.) Additionally, this data allows the River Park Foundation and wildlife agencies to more deeply understand the local micro climate on the mountain and predict when the ceanothus may be blooming, or in need of a little extra water, or the full extent of conditions it can thrive in.

The Installation

With the agreements in place about who would pay for this (a joint effort between all parties) and where we’d put it, it was time to do the work of getting the station up there and installed.

You might ask, what does a “weather station” look like? Here’s a picture of the station itself.

Greg volunteered some of his tools, Jeff Brown lent his old pack frame (originally modified to carry in beer to his wedding decades prior to this trek), and I (Nik) acted as the mule.

DAY 1: Thurs, Nov 14th

After meeting the SDRPF team of Shannon, Chase, Vincent, and Lisa on property owned by the local Audobon Society (Audobon had agreed to let us use a nearby clearing to land the helo in) we started the day’s first task: Moving the gear from the small, shaded parking lot a few hundred yards up the trail to where the helo from Corporate Helicopters (local San Diego company) would land to collect us and our gear.

This included an interpretive panel, a water refill for the tank on SDRPF property, and the heavy metal “basket” that the helicopter would use to transport all our gear.

It’s never boring to watch a helicopter come in and land, and as we heard the whup of the blades we all began to get excited for the day.

After we landed we had a few minutes to wait while the helo flew back and hooked up our basket, then flew it out to us. It was a lovely morning, and Shannon pointed out a beautiful stand of Lakeside Ceonothus, the plant that allowed SDRPF to protect the property!

Once I got onsite, the plan was to drill 4 holes in the rock, fill ‘em with epoxy adhesive, then drop in the bolts, and mount the base plate. I’d come back later with a group to mix and place a concrete pad between baseplate and rock. I was connected via a Telegram chat to SDHGPA members Jeff Brown, Steve Rohrbaugh, Greg Hunter, Brian Stiber, and others who helped with making sure I didn't rush it, skip any steps, or put the station up in the wrong place!

I left the mast about three quarters of the way up the trail, turning around at the last possible minute in order to hustle back down and catch the helicopter out of there. The phrase that kept running through my mind was the obvious one from Predator: "Get to the choppa!"

While I had been up on the mountain mucking about with drilling holes into rock, FedEx tried to deliver the actual weather station to the wrong house back in San Diego, forcing Jeff Brown’s wife to track down the FedEx truck and get our weather station (nice job!) in time for what we thought would be a smooth installation two days later.

Here's the weather station unpacked at Jeff Brown's house for bench testing. Some assembly required:

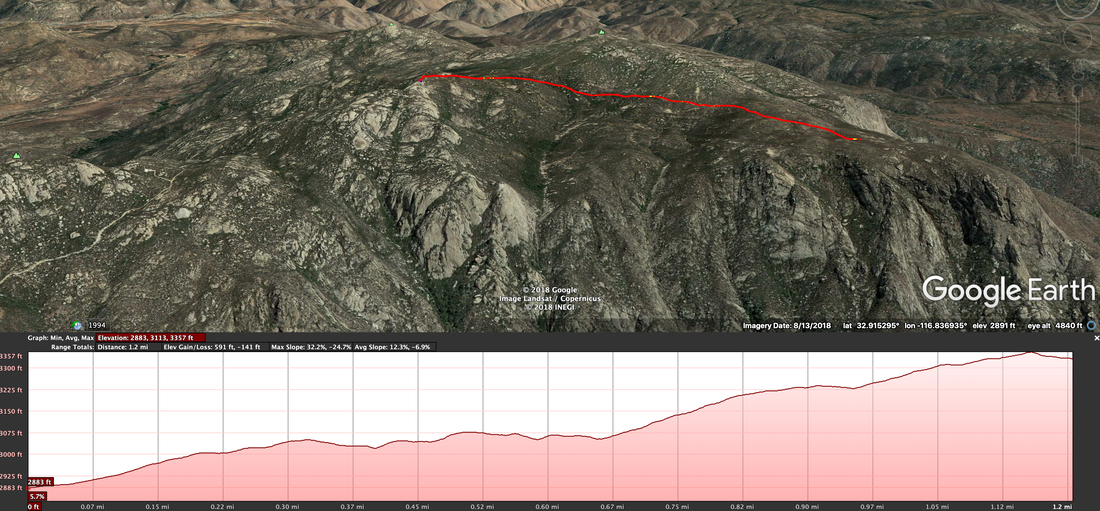

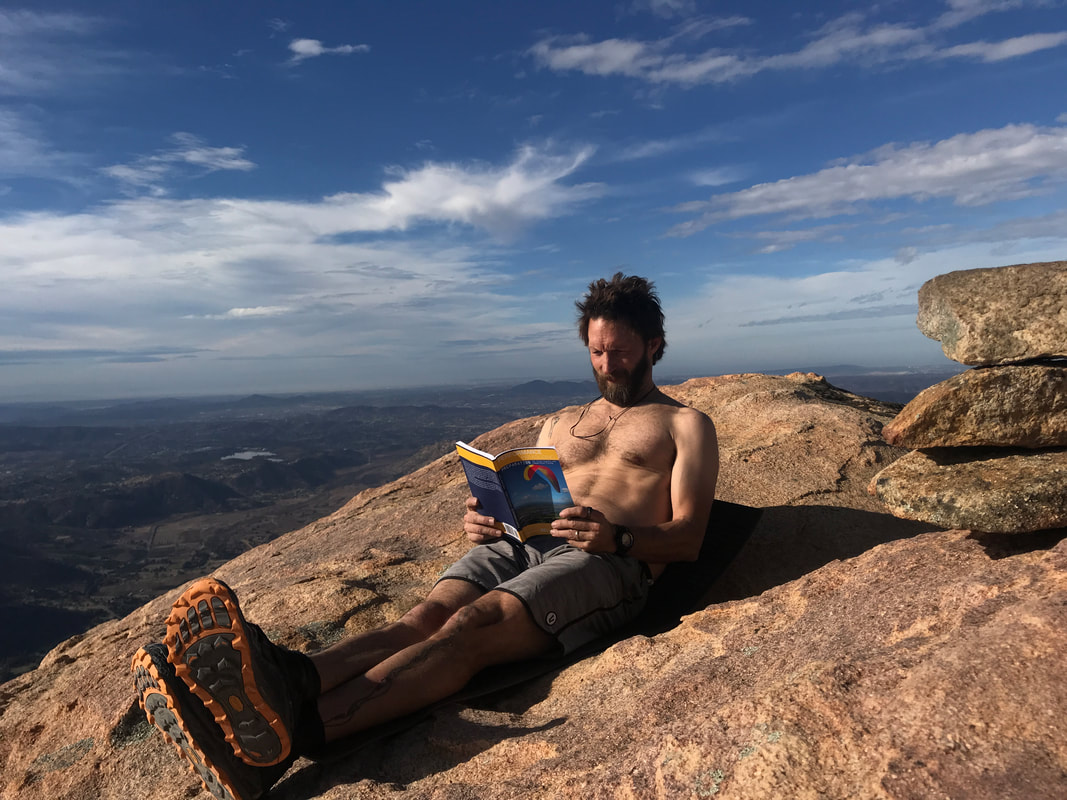

Five local pilots (Jeff Brown, Bill Kimball, Eric & Anthony Karnezis, and myself) met at the El Cajon mountain trailhead to hike in fresh batteries and the weather station itself. At just under 5 miles and 2,600’ of elevation gain, the trail is considered one of the more challenging in San Diego.

We hit our second snag upon realizing that the bolt adhesive wouldn’t set in 45 minutes like I thought it would, but would take at least 24 hours. After some back and forth discussion with Greg and Steve via the El Capitan Weather Station Telegram group, we decided the only course of action was to set the bolts, carry everything not needed for mixing concrete back out, and return another day.

With rain predicted late in the day, we were running out of time to get the concrete mixed and the mast stepped. I was rushing to have it ready by our next club meeting, which was on Thursday. I was at the El Cajon Mountain trailhead at 6:20 AM, and started up the road at a brisk hiking pace. The day started off with distant clouds and a glorious sunrise.

Jeff had designed a neat little sighting device that clamped on to the mast. Using a level, he made sure the sighting device and the wind vane arm lined up, so all I had to do was sight down the device once the mast was stepped, rather than try and get an accurate reading on a thin support arm 12’ up a pole.

Of course, there was a slight kink in the sighting device so that the sighting bar was bent, and I sent back the wrong info to Jeff, but luckily I also took video and he was able to figure out the correct offset angle.

Within a day Jeff had entered the offset, Steve had corralled the data, and a group of pilots had collectively decided we needed to figure out the correlation between what was going on at the Cap with what was happening at Blossom; they are two different places!

See ya in the sky!

Nik Hawks

*While you may wish to hike out to the pole, the weather station is not open to the public, access is not granted for recreational purposes and the preserve is protected habitat for sensitive species.

Please just look at the thing from the end of trail by the old shack and enjoy the stream of data on your phone or at home; no need to break trail in order to see the actual station. It's just a metal pole with metal & plastic boxes mounted on it. :)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed